16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C KathmanduNational

“They turned me into a living corpse”: For victims of the Maoist insurgency, no justice and no peace

Over 13 years after the peace agreement, transitional justice process has largely been held hostage to partisan interests, with both the political parties and Army playing for time..jpg)

Binod Ghimire

It was October 24, 2002. On a crisp autumn afternoon, security forces from Nepal Army and Armed Police stopped a bus Tanka Prasad Tharu was riding on for what was supposed to be a routine check. It was the height of the Maoist insurgency, and Tharu was on his way home to Shreepur, in Bardiya, from Nepalgunj. For reasons he still cannot fathom, Tharu said the soldiers singled him out. He was dragged out of the bus and taken into custody, suspected of having connections with the Maoist rebels.

The country was in a state of emergency and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Ordinance, issued in November 2001, authorised the security forces to take anyone suspected of being ‘terrorists’ into custody for 60 days. Preventive detention could be extended to 90 days without a court order.

In those 90 days, hundreds were tortured and brutalised in the security forces’ detention centres. Tharu was one of them. It has been 17 years since Tharu was taken into custody and 13 years since the war ended, but victims of torture, rape, extrajudicial murder, disappearance and human rights abuses have received no truth, no reconciliation and no justice. All they have are painful memories.

Tharu was taken to the Gulariya District Police Office, where he was asked to admit to being a Maoist. When he denied any connections with the revolutionaries, the torture began.

Police personnel first trod on his hands and kicked him repeatedly in the chest and head. Then, they beat him with bamboo sticks for hours until he fell unconscious.

“When I regained consciousness, I heard a bell in the detention centre striking midnight,” Tharu recalled in an interview with the Post last month. Once the police learned that he had come to, the torture restarted. He was hung upside down and beaten. At night, he would be woken from sleep by a bucketful of freezing water. He was forced to jump barefoot on sharp rocks until he left behind bloody footprints.

The Post met Tharu on November 22, a day after the country marked the 13th anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the landmark accord that ended the 10-year insurgency and pledged to provide justice to victims of torture and crimes against humanity. In a detailed interview, he recounted a horrific story of physical and mental torture, of living in fear for nearly a month in captivation, afraid that he could be killed any moment.

Each day that he was in custody, the police asked him the same question: are you a Maoist?

“Forget being a Maoist, I didn’t even know a single person who was in the party,” he said. “I was ready to bear the pain, but I wasn’t going to lie.”

Tharu wasn’t the only arrestee in the detention centre. Within a week, 64 people, mostly from Bardiya district, were brought in for suspected Maoist ties. Everyone was tortured at some point or the other, said Tharu.

At night, two detainees would be randomly selected and taken out of the detention centre, never to return. Tharu initially thought that they had been released but he soon learned the truth.

“I overheard the policemen say that they were taken to their villages to reveal where the Maoists were. If they cooperated, they were released. Otherwise, they were shot dead and buried on the banks of the Karnali or Babai rivers. Sometimes, they were even buried alive,” he recalled. “I started to see my own corpse lying on the banks of a river.”

But Tharu was lucky. Before he was taken away, a team from the International Committee of the Red Cross arrived at the detention centre. After an hour’s inquiry, officials told Tharu that while they couldn’t tell him when he would be released, they could guarantee that he wouldn’t be murdered. The torture stopped that very day, said Tharu, and he was released a month later.

“I wasn’t the same Tanka Prasad anymore,” he said.

In the 17 years since he was released, Tharu says he hasn’t slept peacefully a single night. His body tends to get numb when he sits or stands in one place for too long and he is on pain medication.

“The police told me that they would turn me into a living corpse, and they did,” he said. “But at least I am alive.”

Tharu is just one among hundreds of torture victims in Bardiya, the district with the highest numbers of disappearances and the second-highest deaths during the insurgency. In 2008, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights had published over 200 cases of disappearance in the district. Subsequently, the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons has received 274 complaints regarding disappearance; among them, it has found 255 to be eligible for detailed investigation. A report by victims’ organisations shows that 499 people from the district lost their lives between 1996 and 2006.

Caught in the middle

In Bardiya, locals, primarily Tharus, were caught between the security forces and the Maoists. While the police and army accused them of being Maoists, the rebels would accuse them of being informants.

Kanhainya Tharu from Thakur Baba Municipality in Bardiya was 22 when he joined the Maoist rebels, who promised freedom from discrimination and a class-less society, in September 2002. Within a year, he was made platoon commander. So it came as a shock to his wife Indra Rati when, in September 2004, she was told that her husband had been arrested by the People’s Liberation Army for violating the Maoists’ moral code.

“There were already threats from the state security forces but then he was arrested by the party where he served selflessly,” she said. “We tried our best to find his whereabouts, but to no avail.”

Their daughter was two-and a-half years old while their son hadn’t even been born when Kanhaiya disappeared.

“Even today, when someone knocks at the door, I think it’s him,” Indra Rati said, her eyes brimming with tears. “If he’s alive, the party needs to produce him. If he’s dead, we need his body.”

Like Bardiya, Sindhupalchok too was among the districts most affected by the insurgency, where reports of disappearance and death stand at over 200 each. And just like in Bardiya, it was civilians and family members who were caught in the middle.

Tulasa Nepal, who is from Kubhinde, lost both her sons in the insurgency. Home to Maoist leader Agni Sapkota, the party had a lot of influence in Kubhinde, which prompted her son Prem Prasad to join the rebels in early 2000. Three years later, she learned that Prem had been killed in a clash with the security forces in Okhaldhunga. She never got to see the dead body, as party members said Prem’s last rites had already been performed because it was impossible to bring his corpse to Sindhupalchok.

Tulasa hadn’t gotten over Prem’s death when her youngest son Dil Prasad, who was just 18, was abducted by the police from Thamel eight months later. He was arrested because his brother was a Maoist fighter. Dil Prasad was never seen again.

“Who can understand the pain of the mother who has witnessed her two children disappear before her eyes?” said Tulasa.

For people like Indra Rati and Tulasa, the disappearance of family members has left them with wounds that refuse to heal. Without a dead body to perform final rites, there is no closure. And without proof of death, family members often end up with other problems. Without a death certificate, property cannot be transferred to spouses or children. Some victims’ families have even asked the local level to issue them death certificates, just so they can move ahead with their lives. But this doesn’t mean that they have come to terms with the disappearance.

“It was a legal compulsion to get the death certificate,” said Sita Basnet, whose husband Krishna Bahadur was disappeared by the Maoists on February 24, 2005. “I won’t accept he is dead until I see his dead body.”

Two-and-a-half decades of waiting

On November 21, 2006, the political parties and the Maoists signed a historic Comprehensive Peace Agreement, ending the decade-long insurgency. Among the agreement’s stipulations, one remains unsatisfied--transitional justice.

The agreement stipulates that both sides—the state and the Maoists—agree to make public, within 60 days of signing, information about the real name, caste, and address of the people disappeared or killed during the war, and inform family members. Thirteen years later, neither the state nor the Maoists have abided by their commitments.

According to an updated Red Cross report, 1,333 people are still missing in connection with the conflict. There are more than double this number of complaints at the disappearance commission, which received 3,157 complaints from victims, with 2,520 classified as genuine after a preliminary probe.

In the name of justice, the government has provided little besides an interim relief of Rs1 million to the families of persons who were victims of enforced disappearance and death. Those who faced torture, sexual violence and forceful displacement haven’t gotten any relief even after 13 years since the peace process began.

According to the agreement, the transitional justice process was to begin within six months and conclude in a few years. However, it took eight years, in 2014, for the government to issue an ordinance for the formation of the truth and disappearance commissions. The commissions themselves were formed a year later.

“The commissions were formed not because parties were willing,” said Ram Bhandari, advisor of the Conflict Victims National Network. “Pressure from victims’ groups, civil society and the international community compelled the government and the parties.”

But in their four years of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons have done little except complaints from victims and their families. This is because the act that formulated the commissions is flawed and the commissions have largely been staffed on the basis of political consensus. In 2014, the Supreme Court had ruled that the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry and Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act be amended in line with Nepal’s commitments to human rights and international standards. And yet, five years later, the government continues to drag its feet.

Earlier this year in April, in an effort to propel the process forward, the government removed the chairpersons and commission members for failing to perform their duties. However, the commissions have remained vacant since then, as the political parties vie to find people who align with their political agendas to fill up the vacancies.

For instance, the parties have made attempts to appoint former attorney general Raman Shrestha and associate professor Ganesh Datta Bhatta to lead the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and reappoint Lokendra Mallick to the disappearance commission. But each time, they encountered strong opposition from conflict victims, civil society and international human rights organisations.

The government in June last year had also prepared a ‘zero draft’ of the amendment bill to collect suggestions from different quarters. But the draft bill was heavily criticised by victims’ groups and human rights organisations and has not moved forward.

Human rights activists who are closely observing Nepal’s transitional justice process say impunity has become a legacy.

Time after time, perpetrators seem to get away with their crimes. In 1990, a committee was formed to investigate the atrocities committed by the state during the first people’s movement, but no perpetrators were ever booked. In 2006, another commission was formed to probe atrocities by the royal government during the second people’s movement. But again, no one was ever prosecuted, despite the fact that the commission identified a number of people as guilty.

The present government, too, is reluctant to make public a probe report prepared by former Supreme Court justice Girish Chandra Lal after investigating cases of human rights violations during the Madhes Movement.

“The government and parties feel that insurgency-era cases can be ignored,” said Nirajan Thapaliya, director of Amnesty International Nepal.

According to Thapaliya, the political parties have put an end to tasks that did not demand accountability--like the army integration. But transitional justice demands the criminal liability of political figures who were either leading the government during the insurgency or the revolutionary forces, said Thapaliya.

Who are the stakeholders?

.jpg)

There are three primary stakeholders in the transitional justice process: the political parties, the security forces (mainly the Nepal Army), and the victims. Though the Maoists, Nepali Congress and security forces fought each other during the insurgency, when it comes to transitional justice, they all stand together. On the other side are the victims.

According to political leaders, it is unfair to single out the political parties for the delay in concluding the transitional justice process, as the Army was the agency that carried out the orders. The Nepal Army says that it is precisely because they only carried out orders that they cannot be held accountable for human rights violations.

However, there has recently been a change in the way the Nepal Army approaches transitional justice. Previously it employed backdoor negotiations to stall the process while making no public comments, but ever since Chief of the Army Staff Purna Chandra Thapa took charge last year, the national defence force has publicly said that it has never been a barrier to the transitional justice process.

“If there are any remaining tasks of the transition, the Nepal Army won’t be a barrier,” Thapa said in a nearly three-hour address to the rank-and-file at Army Headquarters in September. Talking to the Post just after Thapa’s remarks, Brigadier General Bigyan Dev Pandey, the Army spokesperson, said that Thapa is committed to conclude the peace process and the Army will cooperate fully with the transitional justice process.

“A section of people has been spreading the message that the Nepal Army is creating obstacles in the transitional justice process, which is not true,” Pandey said. He further claimed that the Nepal Army had no problems complying with judicial decisions.

However, Geja Sharma Wagle, a security analyst who closely follows the Army, said that Thapa’s statement is just empty rhetoric. The position of the national defence force in the transitional justice process hasn’t been as flexible as Thapa made it out to be.

“The Army claims that human rights violations are issues of individual accountability, not institutional,” said Wagle. “It has been looking for assurance that the leadership itself won’t be prosecuted.”

However, activists and victims believe that there are more than these three stakeholders. Because the 10-year conflict was a civil insurgency, it is the responsibility of everyone--from rights organisations, civil society and the donor-diplomat community--to speak out against continuing impunity and the failure of the state actors to provide a discernible end to the transition.

Though national and international human rights organisations regularly advise and caution the government and the parties, their voices are rarely heard. It is only when they threaten legal action that the government makes piecemeal approaches to mollify them, in the hopes of buying more time, say activists.

However, the voices of civil society and the diplomatic community are rarely heard anymore. According to rights activists, civil society has increasingly become divided along political lines, which has led to a failure to speak out, said Gauri Pradhan, a former member of the National Human Rights Commission.

“It could have also been frustration after repeatedly being dismissed by successive governments,” said Pradhan.

The diplomatic community too has been silent. It was only in January, when the United Nations, together with nine embassies of Western countries, issued a statement urging the Nepal government to clarify its plan for transitional justice.

“I think the diplomatic community doesn’t want to antagonise this powerful government,” said Wagle, referring to the two-thirds majority government of KP Sharma Oli. “But pressure from the international community can be very important in getting the government to take action.”

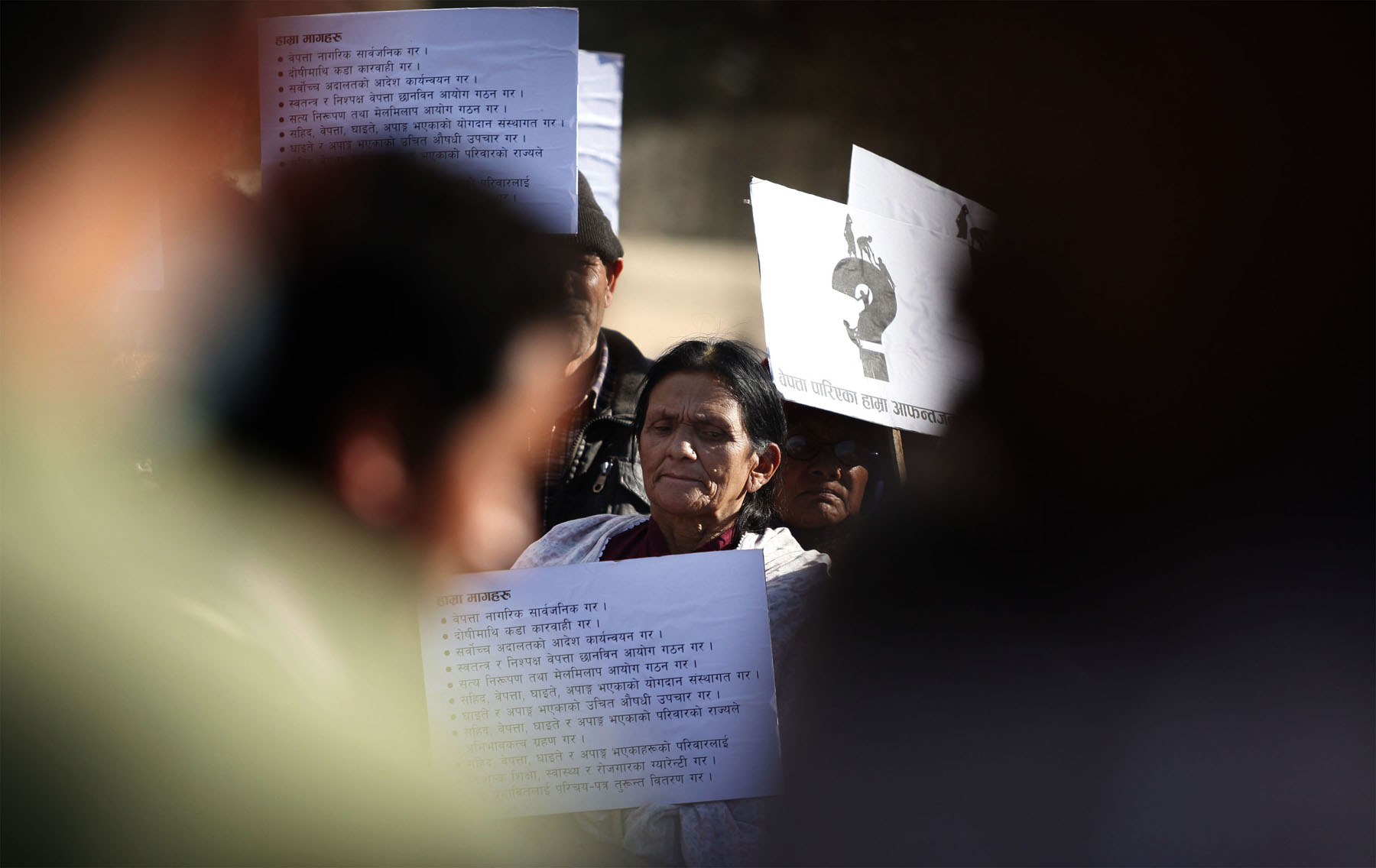

Thirteen years is a long time to continue to pile pressure on governments that are unwilling to listen, let alone take action. Those who are continuing to do so are primarily victims’ groups and human rights organisations. In the last few months, victims’ groups, in collaboration with the National Human Rights Commission, have been holding interaction programmes with cross-party leaders, gaining verbal commitments from many.

Former Maoist commander Pushpa Kamal Dahal, in one such interaction, said that he was ready to take responsibility for all the positive and negative implications of the insurgency and that he is ready to face action for his mistakes. Similarly, Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba has also said that he wants to conclude the transitional justice process soon.

“As the only living signatory to the peace agreement, I am committed to concluding the transitional justice process as demanded by the victims,” Dahal said during a programme held on the 13th anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which was signed in 2006 between Dahal on behalf of the rebel Maoists and Girija Prasad Koirala on behalf of the government.

But this is something that Dahal and Deuba have both said before, so there is room for doubt, say victims.

“We have yet to see their verbal commitments translate into action,” said Bhagiram Chaudhary, chairperson of the Conflict Victims’ Common Platform. “But I also feel the leaders have now understood that they cannot dictate the transitional justice process.”

Chaudhary believes that in the next few months, the amendment to the transitional justice act will finally land before the federal parliament and the two justice commissions will finally have new teams. However, there is no guarantee that the teams will be non-partisan or even effective.

Activists, however, caution against delaying the process for too long.

“Human rights have universal jurisdiction and the world is watching,” said former human rights commission member Pradhan. “Once cases go international, nothing will remain in the hands of the parties.”

.jpg)